The final Isact?

The risk of a strike is long limbo and financial wipe out

And then it was “final”. Alexander Isak will not play for Newcastle again.

Except Isak has a contract - a Premier League contract and one which we can all read for ourselves online.

It has the same core principles that any English employment contract has - rights and obligations.

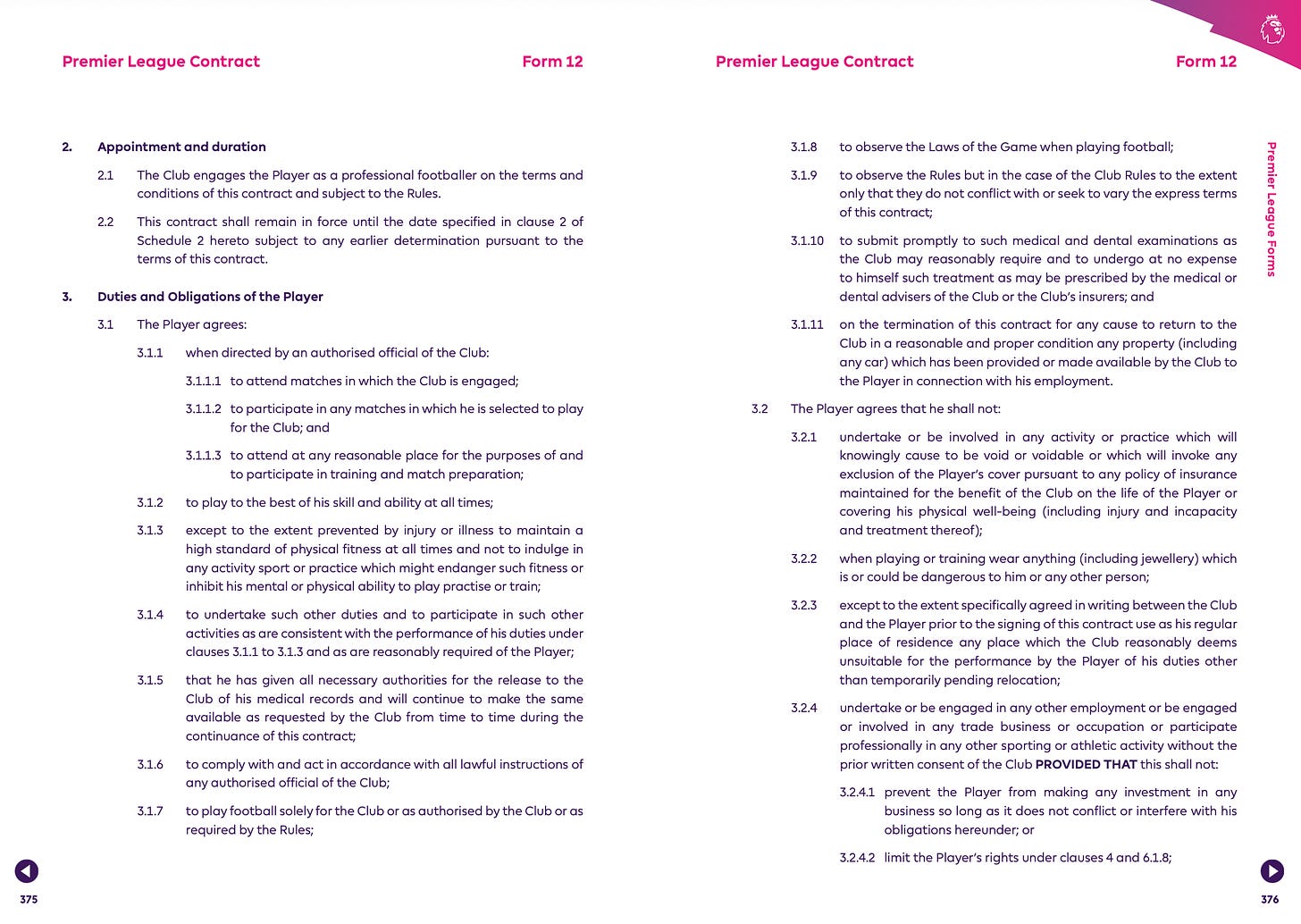

Isak’s contract leaves no room for doubt on his core duties. Clause 3.1.1 obliges the player, when directed by an authorised official of the club, “to attend matches in which the Club is engaged,” “to participate in any matches in which he is selected to play,” and “to attend at any reasonable place for the purposes of and to participate in training and match preparation.” Clause 3.1.2 demands that the player “play to the best of his skill and ability at all times,” while Clause 3.1.6 requires compliance “with all lawful instructions of any authorised official.” The exclusive-services provision in Clause 3.1.7 is reinforced by the “Specificity of Football” clause, which accepts the jurisdiction of the relevant football tribunals for any dispute, including termination and compensation.

These are not ornamental recitals; they are enforceable commitments. A refusal to train is a clear breach of these terms. The remedies are domestic.

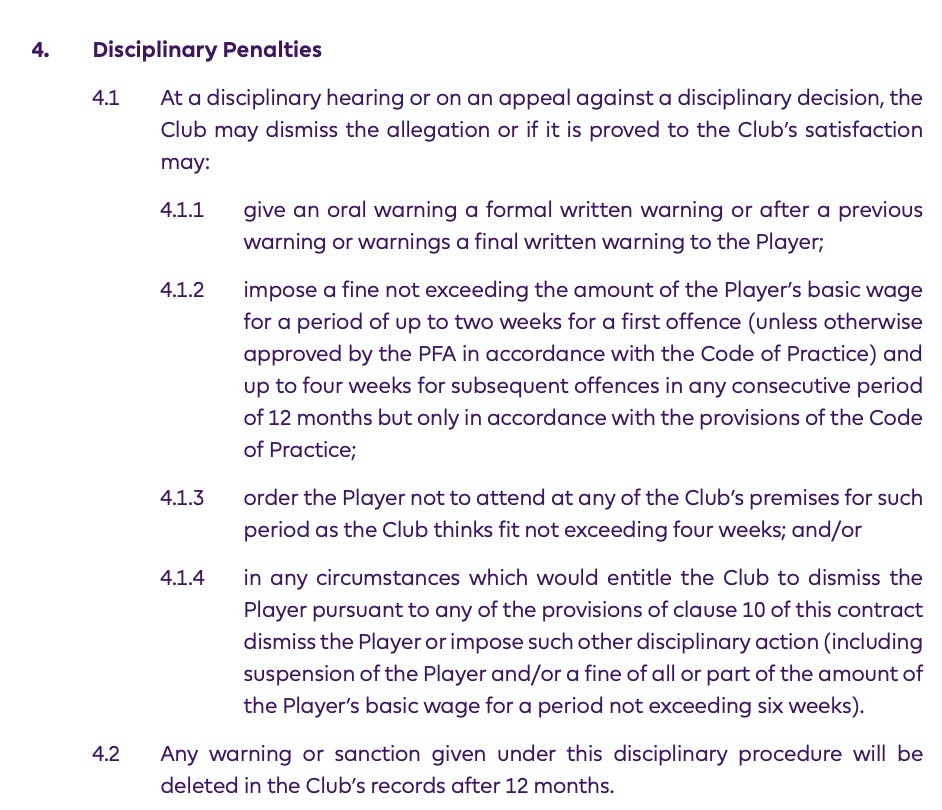

Fines and more

Under the PFA’s disciplinary limits, a club can fine up to two weeks’ wages for each offence and up to four weeks in any 12 month period. Clubs can apply to the PFA for approval of higher fines but, unsurprisingly, the PFA have historically refused to approve. More draconian sanctions - such as suspension from matches or training - are available, but termination is rare in practice because the club would lose its most potent bargaining chip: the player’s registration.

Can Isak terminate?

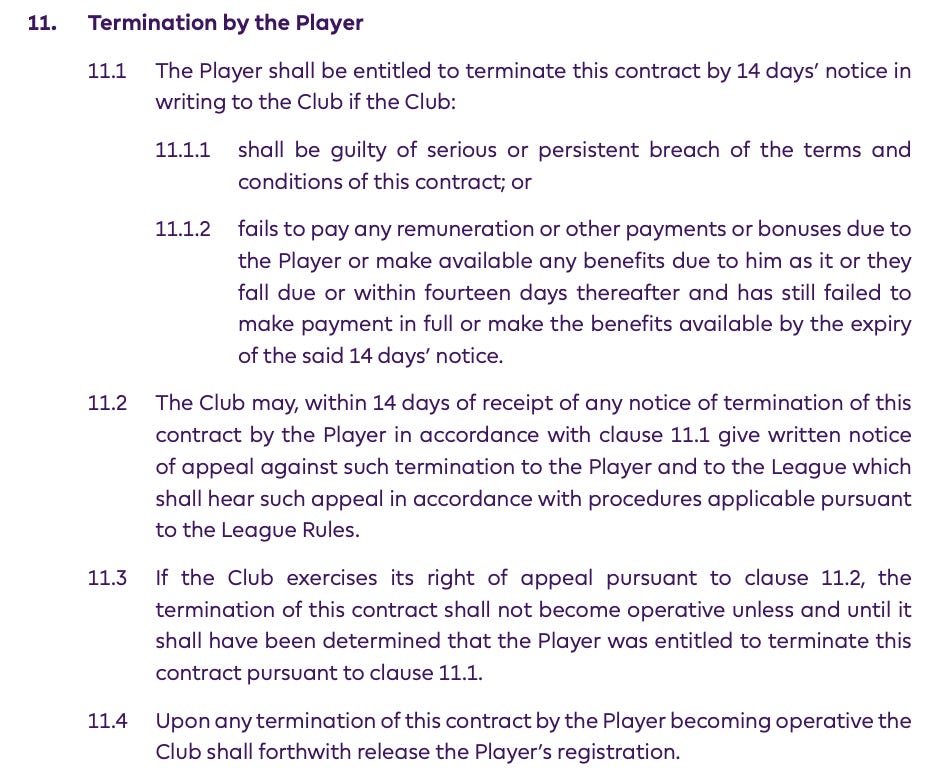

Isak’s right to terminate his contract with a Premier League club is exceptionally narrow.

Under the standard player agreement, early termination by the player is only lawful where there is a clear contractual trigger - most often “just cause” in the form of a material breach by the club, such as persistent non-payment of wages. The “Specificity of Football” clause and the duties provisions in Clause 3 (see above) make plain that the relationship is built on mutual performance for a fixed term, and that any dispute over rights and obligations is to be resolved within football’s own jurisdictional framework - it will not end up in court but in yet another Premier League or FA arbitration room. Without just cause, a unilateral termination would itself be a breach, exposing Isak to disciplinary action, domestic arbitration, and, potentially, a life changing damages claim under English contract law. In practice, a Premier League player cannot simply walk away; absent a club default, the right to terminate is more theoretical than real.

Not a FIFA case - yet

If Alexander Isak were to refuse to train or play in order to force a move within the Premier League, the legal and regulatory context would be very different from the FIFA-driven Diarra framework. In a purely domestic case, there is no International Transfer Certificate to withhold, no automatic joint liability for a new club, and no recourse to the FIFA Football Tribunal. Instead, the battleground is governed by the Premier League’s standard player contract, the FA Rules, and the PFA-negotiated disciplinary code.

The dispute resolution pathway stays within English football’s own structures. A contested disciplinary decision could be referred to the Premier League’s dispute resolution panel under Rule W or X, with a final arbitral award binding on both sides (eventually). Damages claims are theoretically possible under English contract law, but quantifying loss from a training strike is difficult unless the breach has caused specific financial harm. Loss of transfer value if the dispute stretches over numerous windows is more tangible but in any event likely to be beyond Isak’s resources.

That does not mean the risks are trivial. In the short term, the player risks isolation from the first-team environment, reputational damage and a collapse in goodwill with both club and supporters. In the longer term, the club’s control of the player’s registration means that a strike can backfire badly: the selling club can simply refuse to transact, forcing the player to serve out a contract under increasingly strained conditions.

The absence of FIFA-level sanctions does not make a strike a free shot. The real deterrent is subtler but more enduring: once a player crosses the line from negotiation to outright breach, the leverage shifts decisively to the club.

In a league where contractual obligations are detailed, enforceable, and backed by a closed arbitral system, the cold reality is that the walls of the contract close in long before the transfer window ever does.

This reminds me of the Clint Dempsey 'move' where Liverpool made a derisory bid after completely unsettling him and he ended up at Fulham instead.

Great piece Stefan, thanks, very insightful.